Toronto: City Structure Part 1 - The Core and the Periphery

If Toronto has a Transportation-Defined Centre, Where Would it Be?

Around the world, a common pattern that emerges in cities is a sort of transport-defined core and periphery. The core tends to be a relatively small area with greater density, more transport links allowing for easily travel between many points, and policies that are meant to reduce traffic. This is a very practical consideration, particularly for employment, arts and culture, and institutional land uses, because the core idea lets you define a zone of land that is highly accessible from almost anywhere in a greater region as opposed to just a single point at a central station. For example, by taking a suburban train into or to the edge of the core, and then using a variety of local transport options from subway to tramway to get to the final destination, or between, say, an office and a university. More tangential destinations and residential land uses can be concentrated outside of the core, where they may not be connected together directly, but have easy access to destinations within the core, and can at least be travelled between by transferring in the core.

To highlight a few examples we can look at London, Paris and Tokyo.

To be clear, I’m talking about only one definition of core, and arguably in some cases you might even have multiple definitions of core even when looking at transport — for example in London, the congestion charge zone is probably one version of core.

London

In London, you could argue the core is fairly well-defined by the London Underground’s Circle line, which encircles central parts of the city (albeit extending much further to the west than to the east, where it tightly encircles the city of London).

Not only is this definition of core reasonable because there is a nice rail line running around the perimeter, but because the major rail terminals in London largely all exist at the edges of the core. Thus, you can get to the edge of the core on a suburban train, but then often need to switch to one of the underground lines that form a dense web through the area, or a bus, or maybe walk or cycle to your final destination because the core here is only roughly 8 kilometres east-west and 2.5 kilometres north-south (it’s obviously not a perfect rectangle or circle!). It should be noted that the core has become more permeable over time, as Thameslink and the Elizabeth line mean suburban trains can pass straight through the centre of the city.

Paris

In Paris, the core is pretty clearly Paris itself, which forms the centre of the greater Ile-de-France capital region. Paris proper is encircled by the Peripherique ring road and by tram T3, which is slowly getting closer and closer to being a full circle.

Now, the dynamics of the core in Paris are a bit different. Unlike in London, our definition of core in Paris does include the major rail termini, which are about halfway towards the centre (the core of Paris is a circle with a diameter of roughly 9 kilometres). What I think is more important and what highlights the core is that this is where the vast majority of the metro network is concentrated. (The huge Grand Paris Express project is all about expanding the metro to areas outside of the core of Paris, including with the Line 15 loop, which is quite far out).

Of course, like with Thameslink and the Elizabeth line in London, the Paris RER network allows suburban train services to cross the city centre (and while London has just 2 pairs of cross-city tracks, Paris has 4 and a half — thanks to some sharing between the RER B and D). I think Paris makes the mental definition of core even easier because it’s mostly just where the area which is extremely densely served by the metro network, meaning that in the core of Paris it’s quite easy to get almost anywhere else in the core of Paris, while outside of the core you are limited more to a few radial tram, metro, and RER services, which are growing more connected with various new age projects. It’s sort of like a ball with a number of strings flying off it — mostly representing the suburban rail and RER lines into the suburbs.

Tokyo

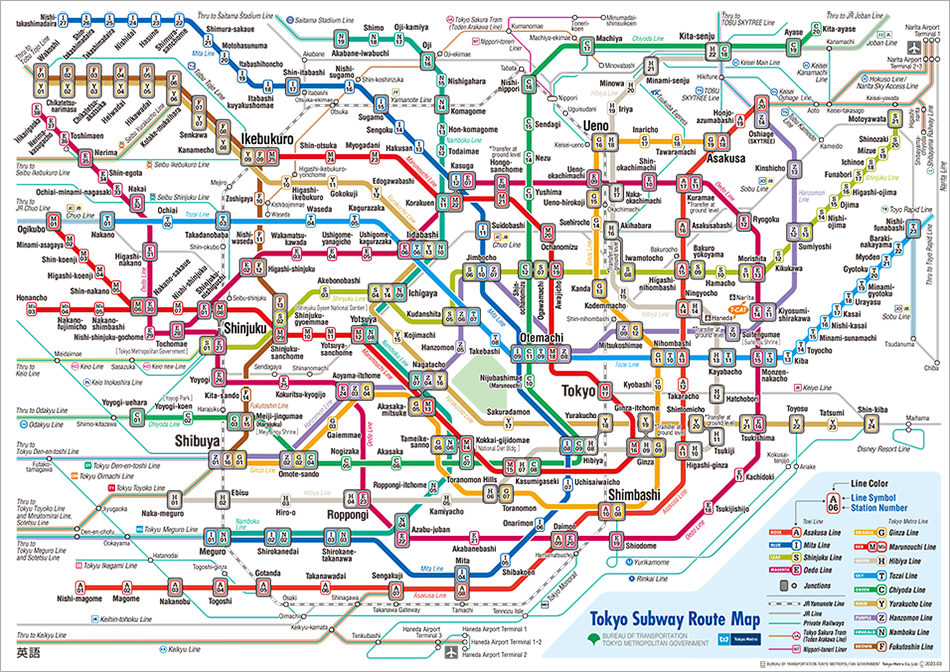

In Tokyo, like in London, the core is probably best defined by a central rail line, in this case the Yamanote line, which encircles the centre of the city, and which has several central business districts along itself.

Like in London, the major rail terminals are located at the edge of the Yamanote line, and so the line serves to connect people between the various suburban rail lines. The subway lines thus quite explicitly serve a role connecting the areas within the Yamanote loop. However, unlike London and even Paris, the core of the subway network in Tokyo combines the roles of RER / Elizabeth line, and Underground / Metro, as the majority of lines allow suburban trains to cross onto them and use them to cross the city centre. There are lines like the Ginza line that do not enable this, but it means that more than the other cities the suburbs of Tokyo are well connected to destinations within the core. The Yamanote loop is large, running about 12 kilometres north-south, and 6 kilometres east-west.

Toronto?

I’ve spent a lot of time thinking about how this core and periphery model fits Toronto, because I think it’s important for thinking about all kinds of urban issues.

Where should the densest development be concentrated?

Where is land the most scarce?

Where should we focus on densifying the transport network?

Where might a congestion charge zone make sense?

Where can offices or major sites be located so that people can access them from anywhere in the region?

Where can we most dramatically reduce car parking in the region?

So where do I think we can draw the borders of the core in Toronto? Unlike in London or Tokyo, we don’t have a ring railway, and we also lack a ring road like Paris. Instead, I think it makes the most sense to draw an area based on the major transport interchanges that will exist around the city’s core. What’s fascinating is that most of these interchanges don’t even exist today: most are currently under construction. In some ways, I think this means that most people still don’t conceptualize these interchanges as being the enormous hubs they will be, several being secondary in scale only to Union Station — and the geographic and real estate implications of this. This is reinforced with the current lack of GO service. While many of these stations do see several trains per hour for most of the day — someday we can expect train frequencies in line with rapid transit, as additional transit capacity is increasingly weighted towards improvements to GO, which will be much higher value investments compared to new rapid transit lines, particularly given the high prices paid for rapid transit in the GTHA.

The Core.

To the east and west of downtown Toronto, it makes sense to look at the major GO - subway interchange stations, which each combine four tracks for GO (meaning either two lines headed to different places, or local and express service) and subway access. In fact, they each also include some level of streetcar access (at least they should), meaning that like with Union, all of Toronto’s different rail transit modes meet at these locations.

Each of these stations will have enormous transport capacity — much higher than Bloor-Yonge, and yet none of them have development and density that is even a fraction of that seen at Toronto’s most important subway interchange. What’s more is that since each of these involve a GO station with 300+ metre long platforms, each complex is physically much larger than a subway interchange, and this larger footprint allows for more developments to directly abut and connect to the stations.

What’s cool about each of these stations is that they are accessible with a single transfer from nearly anywhere on the subway or regional train networks, making them slightly less prime location wise than Union, but not by much. If I was a property developer trying to site a prime development, these would probably be the places I was looking at most closely today, because while they are less well-connected than Union, the development potential is much better, because there is so little around any of these sites today — the gap between the expected appropriate level of development and what exists is much larger than in the city centre.

These stations are:

Bloor-Dundas West

Exhibition

East Harbour

Main Street-Danforth

I know I keep banging the drum about these locations, but they really could not be flying under the radar more given the enormous amount of transport infrastructure each will have. While a location like Vaughan Metropolitan Centre has numerous high rises despite being the site of only a single terminal subway station, each of these has a subway station, four GO tracks, and streetcars running into it.

An interesting note is that both Exhibition and Bloor-Dundas West are likely to become even more important hubs, appropriate as the entire GTHA region is biased to the west. In both cases, a new rail station is planned or under construction nearby: For Exhibition that is King Liberty station, adding connectivity about 400 metres to the north on the Kitchener line. 400 metres east of Bloor-Dundas West, a new station is being added on the Barrie line at Lansdowne, which will add more connectivity to this larger area.

Now, originally I thought it made sense to define the core simply by these “gateway” train stations, but I think it makes sense for the core to extend further north than Bloor, especially with the growing intensification of St. Clair and Eglinton (particularly at Yonge street), so I think it makes sense to consider the northern border of the regional core to exist along Eglinton from Eglinton West to Don Mills, with the interchange stations between the Crosstown, both legs of Line 1, and the Ontario line being the hubs defining this border. This makes the core area similar in size to the other cities we looked at, running about 10 kilometres east-west and 7 kilometres north-south. These stations are all less well-connected regionally than the “gateway” stations because they lack GO access, so any GO passenger is going to need to transfer to the subway to get to them. Therefore, it makes sense for these nodes to be important in the Toronto context, but probably not regionally.

Now, much of the area enclosed by this core area is old Toronto and its pleasant old urbanity. This is a great base to build off of to create a modern urbane regional core, because there is a somewhat higher base level of density, a greater degree of mixed-use development, and narrower streets. Much of this area is filled with more fine-grained development than areas further out.

As far as where I’d draw the precise borders of the core, I am not so prescriptive. It seems sensible to have the lake as a southern border and Lawrence as a norther border. To the west, it seems like including the Junction makes sense, given its growth and urbanity, however to the east I think the Beaches probably should not be included, given how difficult they are to get to from any major rail or rapid transit line without a long walk or a local bus or streetcar connection.

To close out this article (as evidenced by the title, I plan on coming back to Toronto’s “Urban Structure” in lots of future posts) I want to talk about some transport and urban development initiatives that makes sense in and for the urban core area.

Cycling and Pedestrian Infrastructure

Within the regional core, we should make cycling and walking great options that not only feel consistently safe, but consistently lovely. These areas have the highest numbers of cyclists and pedestrians in the region, and so they make a lot of sense as places to invest in more public plazas and parks, and not just functional but attractive places to walk and bike. Perhaps we could even do a “rail viewing platform” like Melbourne!

From a cycletrack perspective, it seems reasonable to expect a safe and fast cycling trip between any two points in the core.

Automobiles

While the obvious policy to implement is some sort of congestion charge — that seems like it will be at least a decade away based on the political winds, so in the meantime, another policy which could have a similar impact is road space reductions, and parking reductions in the core. This is already happening because as density and population are increasing, parking is growing slowly at most, with many new developments having almost no parking, and many surface parking lots being replaced.

Local Higher-Order Transit

For one, north of Bloor we have almost no streetcars. I think it might be worth considering filling the gap with new biarticulated trolleybus lines, particularly running north-south where there are currently few streetcar routes, for example on Ossington, and on Bathurst and Dufferin once the city comes to its senses.

World: A Challenger to the Tram Arrives.

If you’re new here, Next Metro is a blog about public transit around the world — from technology to planning. Subscribe for new articles every week!

Biarticulated trolleybuses would have capacity not far off of the streetcars and could benefit from the TTC’s existing overhead line capabilities. Such vehicles would be well-suited to the many hills particularly north of Bloor. Routes such as this would help encourage development to distribute across the core as opposed to simply concentrating along rapid transit or at interchanges.

Streetcar access should also be improved. I assume the Broadview streetcar extension will get built for East Harbour eventually, but we should also make sure the western extension of the streetcar routes to Exhibition happens to and up Dufferin to King street.

Rapid Transit

Rapid transit within the zone is actually a pretty effective grid, with diagonal GO lines extending to Eglinton in the west and Danforth in the east. I think the main goals (and these are longer term) are taking the Ontario line towards Bloor-Dundas West (making that huge hub even bigger as the first place in Toronto with local and express GO services intersecting a subway interchange), some sort of rapid transit along College, and between the Kitchener rail line and University subway line. Of course, we also should modernize all of our rapid transit with platform screen doors and enhanced stations with more entrances, and the concept of a core could highlight where to prioritize these improvements.

Regional Rail

The big thing to consider for regional rail is additional stations in the core area, where the high density of destinations justifies the highest density of stations in the region. Here are some stations I think should be considered.

Greenwood on the Stouffville line (it’s critical that the stopping patterns on the Lakeshore East and Stouffville lines are also rationalized.)

Sherbourne and Spadina on as many lines as possible.

A Roncesvalles station on the Lakeshore West line.

We should also be seriously trying to get a rail service started on the midtown line. My personal preference is to not do this using GO transit standards, and instead building it to be similar to Ottawa's O-Train line 2, with smaller trains, level boarding, and multiple units from the beginning. Such a line would cut right across the urban core, and enable new diagonal trips from north of Bloor to north Scarborough.

So that’s how I think I’d define an “urban core” for Toronto, why it matters, and how I think we ought to think of its transport development.

Instead of working on platform screen doors and more station access, the TTC, as well as transit advocates should focus on speeding up services. Streetcars here are a joke by global standards in terms of average speed and service quality (priority over cars, platforms that protect riders from traffic and allow level boarding, tracks that don’t require somebody to get out and move the switch physically with a stick).

I also ride line 1 down from the hwy 407 - pioneer village area frequently, and it is demeaning as a transit rider on the portion between Sheppard west and Glencairn where the train barely scrapes 30 km/h while in a highway median and you watch all the traffic fly by at 3-8x the speed. They really need to redo the tracks or rehab them or something, the trains should be able to get up to 70 at least on the allen rd section.

It’s one of the reasons why the west extension doesn’t get much ridership, anybody who lives up there is going to take the go train downtown because it’s more than twice as fast.

tldr: Transit agencies in TO shouldn’t focus replica resources on quality of life improvements like platform screen doors, but look to improve their speed and reliability

Excellent article Reese. This is an important perspective that's been largely overlooked in TO transit planning, at least afaik. An appropriate focus on this has the potentional to solve, or at least mitigate, a lot of TO's transit woes. The needs for, and complaints about, transit are very different for the core vs the non-core.

Ignoring this benefits no-one (other than, perhaps, making everyone on both sides equally dislike transit). I note with approval your decision to exclude The Beaches from your 'core' based on transit service which, I would add, is equally true on the other end of the line as well (examples below).

I admit to being quite disappointed with NJB's recent contribution asking why TO's streetcars are "SO BAD", as he focused almost entirely on the core, and for some reason felt entitled to condescendingly and unfairly slam 'suburbanites' as anti-transit car lovers - without ever acknowledging their legitimate transit needs and grievances, nor the impact decisions re: transit in the core make on them.

A large part of this, imo, comes from TO's illogical decision (historically) to use only local transit to service the outer boroughs of the city, and on top of that reducing that service when this approach creates problems in the core. The 501 into the Beaches is a perfect case in point, and this applies equally to both ends. Labelling the people outside the core, whose only option is often poorly designed abysmal service, as 'anti-transit' 'suburbanites' creates divisions and animosity where none is necessary. If only we attempted to design good-faith transit solutions that actually work for people in all areas this tension could disappear.

It seems lost on some transit advocates that a good number of the people complaining are in their cars in the first place because transit in their area is unuseable (e.g. needing to use local transit to travel long distances) and they've been left literally no other options (unless 90-180+ minute commutes each way are considered acceptable). For instance, the decision to remove or reduce parking in the outer areas where suburbanites connect to transit in the core makes no sense if your actual objective is to increase transit use. If, however, your goal is an actual war on the car and anyone who drives one (which is how I've heard some transit advocates/planners describe it), it makes perfect sense.

Two great examples from the archives, covering both ends of the 501 illustrate this nicely:

The West end:

"An unauthorized sequel to Waiting for Godot. With apologies to Samuel Beckett.": https://spacing.ca/toronto/2008/03/06/waiting-for-501/

The Beaches:

(Google AI overview:)

"Direct Action:

On occasion, residents have taken direct action to prevent the streetcar from short-turning. This has included physically preventing the streetcar from turning back before reaching its destination, effectively hijacking the streetcar to ensure it completes its full route.

Historical Context:

The issue of short-turns on the 501 Queen has been a concern since the late 1970s, with residents using phrases like "they can get a man to the moon, so why can't they get a streetcar to Lee Avenue?" to express their exasperation."

As for NJB lauding Keesmat as transit's lost saviour, again this is only true if one considers it acceptable to pit core vs non-core transit riders, as Keesmat feels entitled to do. I almost envisioned her and Jarett Walker coming to blows over the topic of 'stop spacing', the need for local vs. rapid transit, and mode wars (starts at 8:00 min): https://vimeo.com/85759245