Toronto: A Real Solution to Highway 401 Congestion — an Express Subway.

A subway to Pickering makes much more sense than a 401 Tunnel.

The Ontario government is pushing for a road tunnel under Highway 401. In this post, I’m going to an alternative project that would:

Be faster to build

Let people travel up to 50% faster than they can currently on the 401 (with no traffic) — over 150 kilometres per hour

Roughly double the capacity of the corridor

Completely revolutionize transit on the 401, but also for Scarborough, North York, Etobicoke, Mississauga, Brampton, and Pickering

Cost a fraction as much

A Grand Challenge.

Ontario’s Highway 401 is among the highest capacity and most heavily-used roadways anywhere in the world. On a typical day, over half a million people use its core sections through the GTHA. However, everyone in Toronto, and much of the country knows that driving the 401 for much of the day is a miserable experience. You often don’t come anywhere close to the stated 100 kph speed limit, lanes merge in and out from both directions, traffic is crushing, and it’s hard to even judge when you will arrive anywhere when using the highway. This example trip from Scarborough Town Centre to Yorkdale Mall (around 4PM on a Friday when I am writing this article) is an 18-kilometre journey, that takes about 40 minutes, averaging just 25-kilometres per hour — on a highway.

When you try to make that same trip at midday, Google will tell you it might take as little as 20 minutes (averaging 60 kilometres per hour on a highway signed for 100), but it might still take 40; you basically have to leave expecting it to take almost as long as rush hour because travel times are so variable.

Some time ago, the premier and his government mentioned they were seriously considering a tunnel project, which would likely add some form of express lanes to the highway — this seems like an alluring solution, and it is correct that many cities around the world have urban road tunnels, but there are huge problems in our way.

Scale: For one, most urban road tunnels are in city centre areas, from the Silvertown tunnel in London, to the Yamate tunnel in Tokyo, to the M-30 highway tunnel in Madrid. Tunnels make sense in these environments because of the very high relative land values, but also because since they are in centre city areas (which tend to be compact), none of them are that long. The orbital Yamate tunnel in Tokyo — which took decades to build — would (if “unrolled”) barely reach from Scarborough Town Centre to Yorkdale, much less beyond the borders of Toronto.

Capacity: Another big issue with a road tunnel under Highway 401 is that it would be unlikely to add much capacity — relative to the enormous capacity already present on the route. Most highway tunnels have four lanes (some six), and lower speed limits than a 400-series highway to deal with the space constraints. Tunneling for six lanes and high-speed ones at that would be substantially more expensive (and trucks in the tunnel would almost certainly be a no-go), and since the 401 has at a minimum of 10 - 12 lanes through Toronto, you’d only be expanding capacity by at most 30%. Given the latent demand for east-west road capacity, you could very well complete the project and have the new lanes full in a matter of years, spending billions just to get back to an inconsistent, congested experience.

Time to Build: Of course, building a tunnel that stretches as far as has been proposed — beyond Toronto to suburbs on each end — would be an enormous undertaking. It’s not reasonable to suggest it is impossible, human civilization has built lots of impressive tunnels, but it would likely take well over a decade to build even in the most optimistic case, assuming Toronto got as good at building tunnels as Switzerland or Spain. Realistically this would be a multi-decade project, including years of planning given the scale, all to deliver just 30% more road capacity.

Cost: And then there is the price. This tunnel project would not only require far more tunneling than is required for the typical subway project in Toronto, both in terms of length and “width” of the tunnels, but it would also be riskier, passing through areas with different soil conditions and the like, and much more complex, with the need to site innumerable safety access points, entrances, and exits, all while seriously disrupting the flow of traffic on the 401 for years. It is not unrealistic given the price of subway tunnels in Toronto to suggest it would cost over $50 billion dollars, or perhaps as high as $100 billion dollars, all to add just 30% more road capacity, to be filled a few years after construction. If, as I expect would be the case, people demand “transit” be incorporated into the tunnel, (perhaps as an environmental condition to build the project) in the form of underground bus stations or a massive surface reconfiguration, the cost would be driven even higher.

Tolls: Theres also the issue of tolls. The vast majority of major urban road tunnel projects around the world and even many surface express lane projects in places like Texas and California are tolled. (Unironically, doing tolled express lanes might be unpopular, but it’s probably the only way to actually guarantee you can have a smooth drive on the 401 whenever you want. These could be a big help if you’re running late, or in case of an emergency. But the reality is, the only way to overcome the problem that is high demand and extremely low supply is a toll — as in the US cases). In fact, if you look at the most impressive urban road schemes in the world, like Sydney’s WestConnex, they are predicated on tolls with prices not dissimilar to those seen on Highway 407. The government insists it’s not interested in tolls, and fair enough — because given the prices tolls would have to be, to reasonably offset the cost of such a project, drivers may as well take the 407. The issue is, if you don’t pay for the road with tolls, how will you pay for it? Is it worth putting off constructing several subway lines and tens of hospitals across the province to gain 30% capacity on the 401, which will become congested again soon after?

Ultimately, because so much of the traffic on the 401 passes through the GTHA, from eastern Ontario and Quebec to southwestern Ontario and the US, if the goal was simply to free up space on the 401 with more roads, the most cost-effective plan would be building some beltway north of the city. That could perhaps have a higher speed limit than the 401, and it would surely be several times cheaper, faster, and simpler to build than a tunnel under the existing road alignment; it may also be able to add transport capacity to areas of the GTHA which do not already have access to one of the world’s largest highways. Ideally, this would be the role that Highway 407 plays, but historic errors in selling that road off make the relief capacity of the 407 minor.

At the end of the day, the “401” tunnel also doesn’t make a ton of sense, because if the goal is a “superexpress” route across the city — the only thing that makes sense with a tunnel (each entrance and exit would massively increase the price as smaller more complicated tunnels spiderweb to the surface) — it’s not even clear why you’d follow the 401, instead of drawing a straight line between your start and end point, shortening the tunnel and also potentially taking a route that isn’t directly under a super important transport artery that you don’t want to disrupt.

But this probably isn’t an attractive solution to the premier or the government (at least based on what I’d imagine), because I think they have correctly identified that people want to go to places along the 401, and so building more lanes somewhere else doesn’t directly address that, even if it temporarily lightens traffic. Fortunately, there is something which could and which could be delivered for a fraction of the cost, and far faster than tunnelled 401 lanes — all while providing greater and unique benefits: A 401 Regional Express Subway.

A Regional Express Subway.

While a series of tunnels under a highway like the 401 would be globally unprecedented, risky, very expensive, and a multi-decade proposal, it is reasonable to assume that you could construct a “Regional Express Subway” along the route for less than 20% of the price, with less disruption and risk, in about a decade.

Express Subways are a sort of evolution of the subway technology of old and the “express trains” of a city like New York. Express Subways are much like traditional subways, but with alignments and trains designed for travel at 120, or even 160 kph — similar speeds to GO trains in some parts of Toronto today, and much faster than even the highest conceivable speeds you’ll see on a highway in Ontario. Such lines, sometimes called high-speed metro, are being built in cities from India, to Korea, and across China — under various names.

I think it’s worth reiterating just why transit is a such good idea here. To do so, let me give you an example from my personal life. A transit planner friend was coming to see me in the suburbs of Toronto (in a car — transit planners also do sometimes drive), and remarked that the same roads extending north from Toronto are frequently super congested in York Region, despite sometimes even being wider. Why? Well, in Toronto, basically every suburban arterial has a super frequent bus route that moves tens of thousands of people every day — all of those people not in cars legitimately adds up, and means driving in Toronto is actually often better than its suburbs. Transit people often talk about the space efficiency of transit, but they rarely frame it in a way that makes a lot of sense for suburbanites — who almost all drive at least some of the time!

In a similar sense, a rail line with the capacity to move ~500-800 thousand riders every single day really does have the potential to impact traffic on the 401. Obviously, not everyone on the 401 can jump on a train, but a huge number of people could — particularly those travelling to and from places like Scarborough, North York, and northern Etobicoke, to the major hospitals, malls, and transit lines that are all proximal to the highway. I think it’s lost on people, but a lot of people clearly use the 401 for intracity travel in Toronto, just because its the fastest way to get across the city even with the terrible traffic. For many transit journeys even with start and end points near the 401, the current best transit trip involves riding south to Line 2, across the city, and then back up! Many people who don’t currently use transit for trips in north Toronto probably are either headed to, or are starting from the general vicinity of the 401, and would be happy to take a short bus trip to rail (the buses in Toronto’s inner suburbs are again super frequent), and then be zipped to their destination.

Basically, while you might be able to add 100 thousand cars a day of capacity to the 401, building an express subway along it should easily be able to get well over 100 thousand cars a day off the road (the Sheppard subway moves 50,000 people a day in its pitiful state, and Line 2 moves ~500,000).

The Proposal.

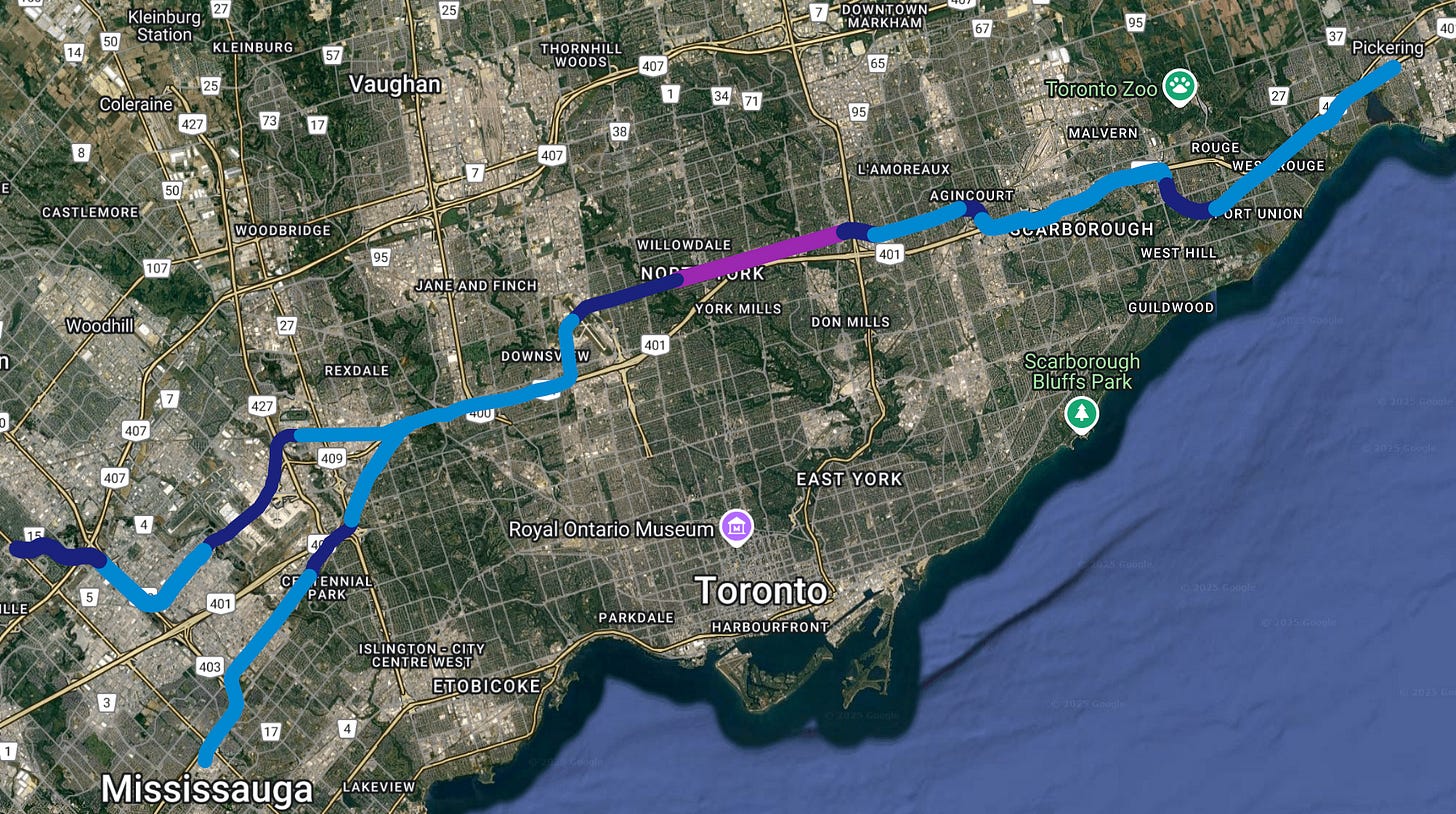

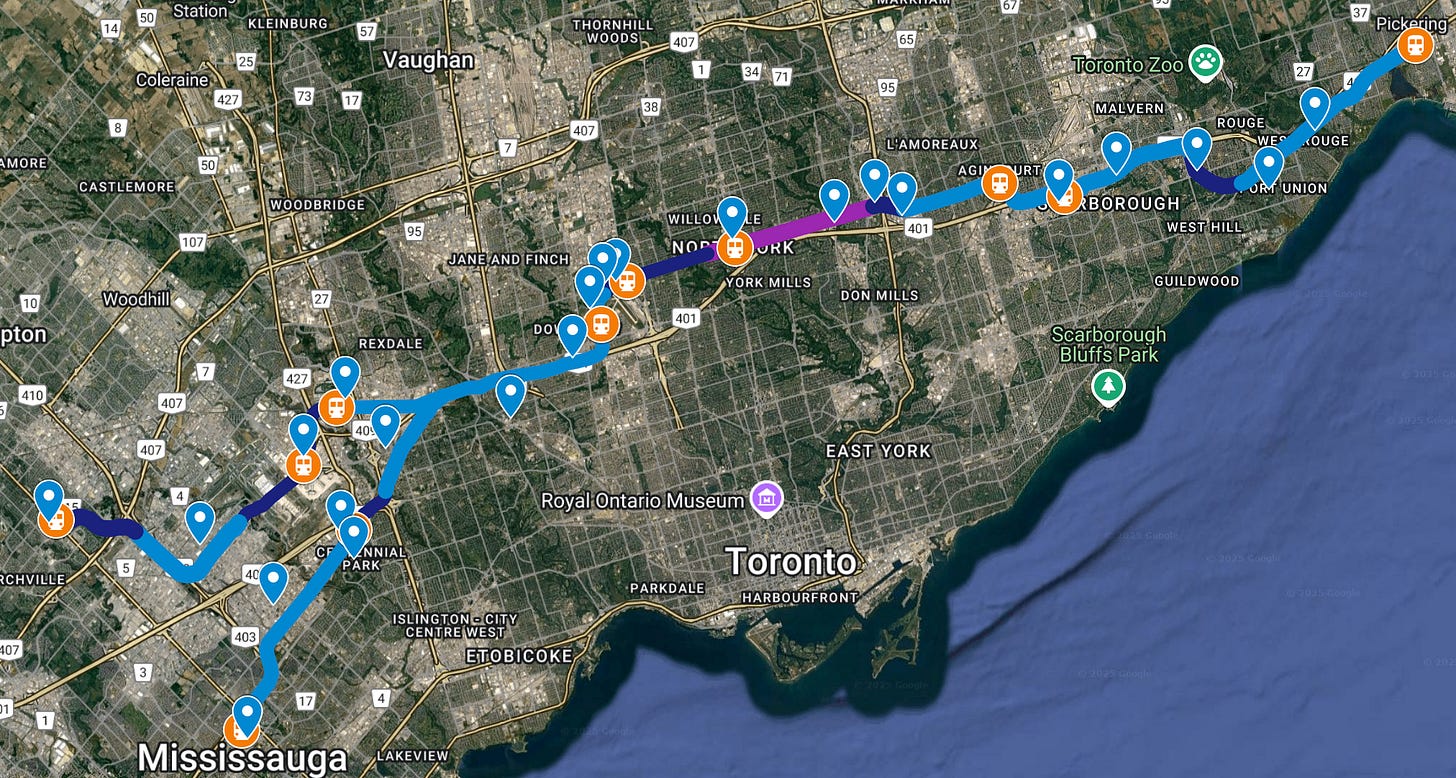

I’d suggest, that instead of a 401 express tunnel, Toronto builds a roughly 50-kilometre express subway line, which would initially stretch from the Mississauga border and Pearson airport in the west, to the University of Toronto Scarborough in the east, but which could be extended in a second phase all the way from Pickering to Mississauga City Centre, and Central Brampton, and beyond if you desired.

The core of the line would combine the current Sheppard subway in Toronto and elements of the government’s proposed Sheppard subway extension to Scarborough, with new segments of track rerouted along the 401 — which is very destination-rich, with Pearson Airport, malls, hospitals, schools, underserved communities, and enormous transit connectivity. Most new segments of the line would be built elevated, like the Ontario Line and Montreal’s dramatic REM project, but strategic tunnels would be built to extend the Sheppard line, pass under Pearson Airport, and connect to central Brampton.

To be clear, the entire line would not literally run on the 401, and almost no stations would be situated at the Highway. The line would sometimes run along the highway between stations, but it would detour off the highway to serve stations in existing, and growing neighbourhoods, as well as to sometimes travel along city streets that closely parallel the 401. This allows cost savings when running along the highway, but better connections to other transit lines, and the many developments that already exist along the route.

I understand people might question building transit along such an inhospitable place as the 401, but I want to point out X things:

Much of the line wouldn’t literally be along the highway

A transit line which is mostly oriented to connecting passengers, who aren’t living at one end and working at the other — is okay. Connections are to be expected, and huge volumes of connections are what drive ridership on existing TTC subway lines.

People and destinations are already along the highway; I wish it wasn’t the case, but it is, and not giving people better transit and connections because they live near a big road feels kind of perverse.

The beauty of a project like this is that it is very friendly to a phased construction approach. Toronto hasn’t done this with a ton of on rapid transit projects in the past, but it’s common around the world. Building phase by phase could shorten the time to getting the first phase open, and also improve construction efficiency by avoiding “boiling the ocean”. An initial phase could be the Sheppard subway extension, taking that line both to Scarborough Town Centre, and to Sheppard West, where a large new yard (potentially with housing on top, as in Hong Kong and Singapore) could be built for the whole line. Further phases east would take the line to Centennial College, the University of Toronto Scarborough campus, and Pickering GO station, while to the west phases would extend to Pearson Airport, Mississauga City Centre, and either Downtown Brampton, or Brampton Gateway Terminal.

Once complete, the project would be the one of the longest rapid transit lines in the Americas, and the longest in Canada at roughly 80 kilometres, with connections to 4 GO lines, the UP Express, subway lines 1 and 2, and the Finch West, Eglinton, and Hurontario light rail lines. The rapid link to Pearson airport would mean fast one-seat rides to the airport from Brampton, Mississauga, North York, Scarborough. and Pickering. It would also connect to numerous major hospitals, offices, shopping centres, transportation hubs, post secondary institutions, and many dense underserved neighbourhoods.

Crossing Toronto from Mississauga to Pickering would now take less than an hour even on days with heavy traffic, and with express trains travellers could go from Scarborough to Pearson, or Brampton to North York in half an hour.

Because so much of the project would be built above the ground, construction could be completed on initial phases in well under a decade, and the entire project could be completed in under fifteen years, as with the REM in Montreal. Utilizing the highway right of way for new aerial guideways — akin again to the REM, or the JFK Airtrain in New York — would reduce costs and speed construction.

Technical Details

The natural question transit regulars will have is how? The Sheppard subway is a TTC subway line, with a top speed of 80 kilometres per hour, a unique rail gauge, and more.

As part of the project, the Sheppard subway would be re-gauged to standard gauge (this has been done in a number of places around the world) and severed from the TTC subway network. The tunnels and third rail electrification system would be used for that portion of the line, but as with many modern Chinese metro lines, new high-speed subway trains would also be equipped for overhead power and would switch to this beyond the existing Sheppard subway when stopping at a station on either end. While you would be speed limited to an extent within the relatively short (5.5km Sheppard subway), that section could probably be modestly sped up, and the rest of the line being newly constructed could be designed for far higher top speeds.

As part of the project, the existing stations would have their platforms extended to their planned six-car length, and platform screen doors would also be installed as with at all new stations. This would enable automated train operation — like on the Ontario line, and Beijing’s high speed driverless subway to the new Daxing airport. Conversions of traditional lines to automated operation has become common practice, having occurred in Paris, Madrid, and Sydney, and given the Sheppard line’s comparative modernity it would be well-suited to this. The automation is important: it enables greater reliability and high frequency at all times, which is critical for a line that is made on the back of connections to other services, sometimes on both ends of the journey. At the same time, having enclosed stations with screen doors, air conditioning, and ventilation would remove most of the negative impacts of being proximal to a highway (though again few stations would literally be along the highway) — like noise and air pollution.

In terms of average speeds, for new sections of the line it seems possible to have average speeds of around 100 kph, as you’ll see in modern Chinese Express Subway lines. The overall line-wide average will probably be pushed down a bit by Sheppard, and a bit more by a wandering alignment that doesn’t enable maximum speed at all times, but you could also push it up by running express trains — which could stop only at interchange stations, skipping others with carefully placed passing tracks — and schedules closely followed by the automated trains. Since so much of the line is above ground, you could build these passing tracks for a small additional cost.

The core of the line (UTSC to Pearson and Renforth) would include 15 kilometres of new tunnel, and 29 kilometres of elevated guideway. The full project from Pickering to central Brampton and Misssissauga would add 8 kilometres of additional tunnel, and 23 kilometres of elevated guideway.

Assuming Toronto could drive prices to the levels seen on the most recent projects in Vancouver on the SkyTrain system (with which this line would bear great resemblance — I’m assuming $500m per kilometre for tunnel, and $375m per kilometre for elevated — both of which are far more than Toronto built for in decades past, and much of the world builds for today), Phase 1 would cost approximately $8B CAD for tunnels, and $11B CAD for guideway. The expanded second phase would add an additional $4B CAD for tunnels and about $9B CAD for guideway. All told, the project should be doable within a similar ~$30B CAD budget envelope as the Ontario line, but delivering far far more kilometres of rapid transit, since so much of the new stuff can be elevated, and even when we’re building tunnels, they don’t need to be deep, and it’s not the kind of high-risk stuff where you’re going under high rises and through dense old urbanity.

This alternative idea needs to be amplified. So far the narrative on the tunnel idea is only ridicule with no solutions. Solid alternatives to 401 are needed and this is a great one.

Ford’s going to want a tunnel win—something tangible he can point to. The best spot to give him one is near the 427, where the 401 hits a major choke point thanks to the Richview Expressway never being built. This part of Etobicoke is one of the few stretches in the GTA that still doesn’t have a collector/express system. A short tunnel here—just a few kilometres—would provide real relief for drivers and deliver a clear political win. Sure, expropriating the mostly industrial land nearby might be cheaper, but a tunnel looks bold and future-focused. It’s the kind of big move Ford Nation likes to see.

Now, let’s be honest: nothing is going to solve 401 traffic. But we can make it a lot less painful as the region grows. A fully built-out Line 4 (Sheppard) would take pressure off the road network—and it’s the kind of transit project Ford could realistically support. Getting the Midtown Line moving—beyond just talk—would help too, especially for crosstown travel.

Speaking of crosstown, that final stretch of Line 5 to Pearson needs to be finalized, along with an extension of Line 6—at least to an UP Express station at Woodbine Racetrack. And while we’re at it, extending Line 2 to Sherway makes sense. Maximizing all east-west transit options is what could actually make a difference here.

And then there’s trucking. Getting more trucks off the 401 and onto the 407—even if it means offering subsidies—is just smart. Every driver stuck behind a convoy knows this. Roads are already subsidized—this would simply direct that funding where it has the most impact.